Multinationals need to be mindful of China’s rapidly changing business environment as they continue to double down in the country, say Jan Borgonjon and James Sinclair.

- According to our China Business Forecast 2022, multinationals continue to double down on their China businesses, regarding China as the main growth opportunity worldwide over the next decade.

- But growth comes amid a rapidly changing political, economic and social climate in China. Multinationals have to be clear whether they are operating in “open” or “restricted” sectors, and prepare for change accordingly.

- Meanwhile, local competition is becoming formidable both in terms of scale and capabilities, and sophisticated technology ecosystems are forming to drive technology development in China.

*** This is the first part in a two-part series. In this first part, we look at how 2021 was a significant year in terms of the changing business environment for multinationals operating in China. In the second part, we will discuss how multinationals should respond to the new business landscape ***.

If there is one resounding message from our annual survey of China country managers working for multinationals this year, it is that they continue to be believe in the China opportunity, and are doubling down on their China businesses.

Our China Business Forecast interviewed almost 300 managers in October and November 2021 across a broad range of sectors. More than a quarter said that China now accounted for more than 20% of global sales, while almost a third said their Chinese business now accounted for more than 20% of profits. Driven by consumption growth and the modernization of the economy, more than four fifths said that China will be their number one or two top market worldwide by 2030.

A tumultuous year

But the opportunity presented by China comes against the backdrop of a new geopolitical era and rapid economic, regulatory and social change in China.

Through the course of 2021, we have seen Beijing introduce a succession of often quite sudden policy initiatives, ranging from the overarching “dual circulation” and “common prosperity” policy drives, to crackdowns on Big-Tech, for-profit tutoring and online gaming, to tighter controls over the highly-leveraged property sector and the potential default of the developer Evergrande. Meanwhile, companies have had to struggle with supply chain disruptions and power shortages in some regions.

Understanding what this all means, and what to do about it, would have been difficult for multinationals operating in China at any point in time. But given the travel restrictions imposed by Beijing in response to the pandemic, this has become particularly challenging for executives stationed at global headquarters outside China.

From our vantage point, the raft of policy initiatives, while interventionist and severe by Western norms, do make a lot of sense in the context of Beijing’s development goals. Moreover, Beijing is often acting in response to concerns that many societies around the world share.

Nevertheless, multinationals do need to be aware that the rules of engagement in China are changing fast. Geopolitics and domestic policy are combining with the strengthening of local competition and emergence of sophisticated technology ecosystems to drive a fundamental shift in the business environment, affecting business practices and business models.

In the following paragraphs we will look at these changes, and how multinationals need to determine what the implications are for them.

A changing policy environment

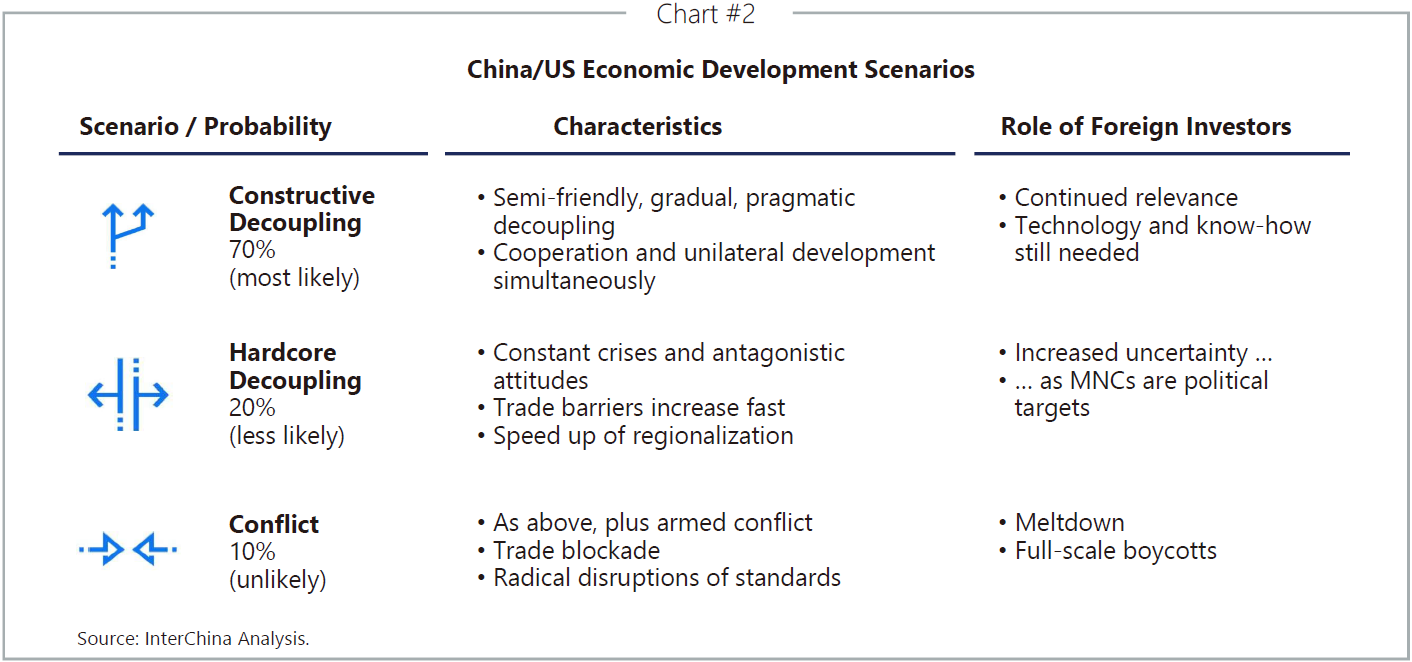

Multinationals that we polled agree that some form of economic decoupling of China from the West is undoubtedly here to stay. However, the consensus is that a constructive, gradual and pragmatic decoupling is the most likely outcome in the years ahead. While international investors are expected to continue to have relevance in China, with their technology and know-how still in demand, Beijing will move to end its reliance on Western countries in key technology areas.

In the pursuit of its development goals, China’s policy priorities are mainly domestic. The key economic priority is a shift from a ‘quantity-driven economy’ (= GDP growth, volumes, low cost, cheap labour) to a ‘quality-driven economy’ (stronger regulatory compliance, financial sustainability, higher value-added output, and more services).

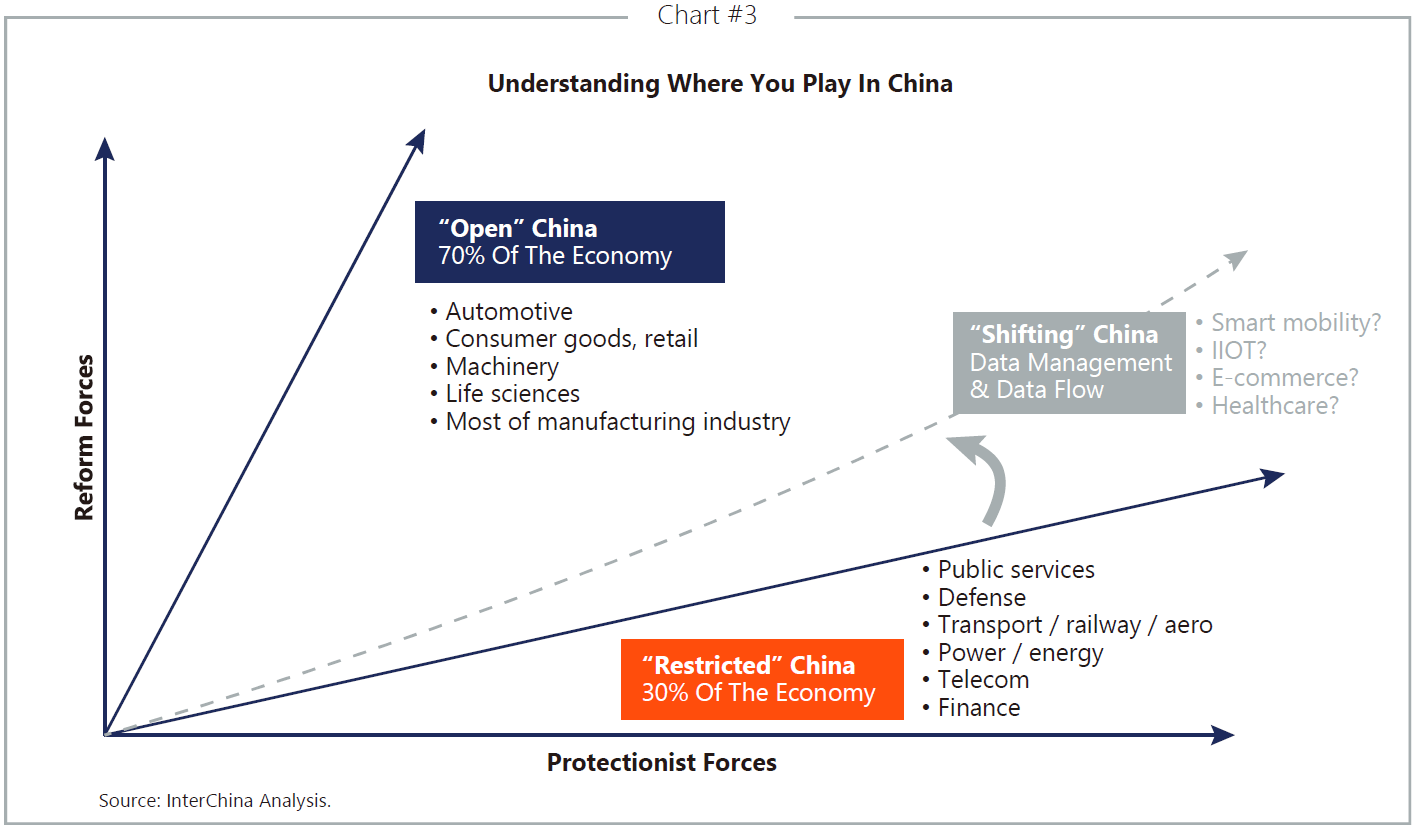

While this shift affects all multinationals operating in China, different multinationals are facing profoundly different challenges. They divide into two groups, depending on the level of regulatory control over their sector. Determining whether you are in one group or the other, or have different business units in different groups, and how this might develop over time, is critical to figuring out the right China strategy.

- “Open” sectors:More subject to reform forces, with companies operating in these sectors generally free to compete. These sectors account for about 70% of China’s economy, and include automotive, consumer goods, retail, life sciences, machinery and most of the manufacturing industry.

- “Restricted” sectors: More subject to protectionist forces, and tend to be dominated by state-owned enterprise. These sectors account for about 30% of China’s economy, and span public services, defence, transport, aeronautics, power, energy, telecoms, financial services, etc.

The key challenge for multinationals operating in “restricted” sectors is market access, while the imperative for multinationals in “open” sectors is to improve their competitiveness. We will return to the implications for international companies in more detail next time, in part two of this article.

Strengthening local competition

Local competition is becoming formidable both in terms of scale and capabilities, where capabilities span customer insight, product development, technology differentiation and service delivery.

Multinationals need to be particularly mindful of Beijing’s continued drive to build national champions, motivated by the need for domestic consolidation and stronger regulatory compliance (across a range of standards including tax, social security, environmental protection, and security).

National champions range from the likes of COSCO in shipping, CNBM in building materials and SinoMach in machinery, to CSSC in shipbuilding, BaoWu in steel, ChemChina in chemicals and China Electric Equipment in power. Many of these companies are already bigger than their largest global competitors, while they still basically only focus on the Chinese market.

The competitiveness of Chinese companies is not confined to national champions in industrial sectors. In the consumer space, for example, a plethora of local brands are emerging to challenge the multinational incumbents. They have become adept at understanding their consumers, developing differentiated solutions and marketing creatively. And all this at rapid speed.

In our survey, we found that almost three quarters of multinationals operating in China expected to lose their origin advantage (the status gained from being an international company) and technological superiority (provided by their global capabilities) within just five years, and almost all by 2030. No longer able to trade on their international origin or technological edge, multinationals will have to increasingly compete on their local merits.

Indeed, as the China President of a multinational chemicals group told us: “The opportunity is there for multinationals to take, but China requires full commitment. You’re either at the table deciding on the menu, or you’re on the menu.”

Technology ecosystems

Although no longer discussed in public, the centrepiece of Beijing’s industrial and technology planning is the “Made In China 2025” blueprint, defining 10 strategic sectors in which Chinese firms should transition from acquiring technology to making innovation breakthroughs and thereby achieving self-sufficiency and market share targets. Progress is being made in many of these sectors, with local players now taking a 90% share in China’s power transmission equipment market, and 80% in new energy vehicles.

Indeed, the progress that China is making in technology development is profound. Across a myriad of emerging high-tech products, China is already a technology leader or rapidly closing the gap. Over the coming years, China will become the global trendsetter in many high-tech industries, developing these industries rapidly and taking significant global share.

Technology ecosystems are forming to drive this technology development in China. Larger companies know that they cannot innovate sufficiently rapidly and successfully themselves. This is especially the case given that the boundaries between different sectoral domains are disappearing, making the technologies of one domain relevant to many others.

These technology ecosystems are evolving in many ways: Companies are acquiring technologies across boundaries to form new synergies, models and solutions. Mature companies are investing in and incubating promising start-ups. Alliances are forming between companies to link capabilities and deliver combined solutions to customers. These ecosystems are visionary, dynamic and flexible, and they are working.

Some of the most advanced in building ecosystems are the Big-Tech operators, including the likes of Baidu, Alibaba, JD.com and Tencent. JD.com today covers online retail, big data analytics, logistics and financial services, while Tencent’s interests include social networking, gaming, fintech, business services, online advertising and retail.

Summary

Although the decoupling drive is here to stay, it is worth reiterating that most China country managers of multinationals believe it will be a constructive and pragmatic decoupling. That means multinationals will continue to be relevant in China, but that they will need to be ever more mindful of the influence of government policy on the business environment. Many will need to follow new paths and make unprecedented decisions. Alignment and communication between the China leadership and their global headquarters will become both more challenging yet ever more critical.

*** This is the first part in a two-part series. In the second part, we will discuss how multinationals should respond to the new business landscape, addressing the following set of strategic questions:

- Where does the ‘new China’ stand in my global strategy in terms of the market, competition and scale?

- What does it mean to ‘be Chinese’ for our company, and do I need to decouple from China?

- Am I fully capturing the Chinese innovation boom and do I understand (and need to be a part of) new local technology ecosystems?

- What is the role of inorganic growth for our business, and do I need to consider M&A activity?

- What governance models will allow our business to be close to China but still retain our corporate DNA?

***

English

English